Rise and fall of FC Barcelona. A political economic explanation

The club’s performance in the last two decades can be largely explained by the adaptations of the national and European leagues to the globalization of football.

Image credit: Pexels

Image credit: PexelsFC Barcelona will not be in the round of 16 of the Champions League. The last time the Catalan club did not pass the group stage was in the 2000/2001 season, shortly before the current president Joan Laporta began the most glorious period of the club. For the last 20 years, Barcelona fans have become accustomed to winning to the point of considering a failure not to reach the Champions League final. No wonder. Shortly after being eliminated by Milan and Leeds United in 2001, FC Barcelona experienced an unprecedented revolution. In just a few years, its budget doubled, an increase unmatched by any other European club. The club would attract players the size of Ronaldinho, Henry or Deco, with whom it would win four Champions Leagues in ten years.

Now, with the new situation - a discreet classification in the Spanish league and the elimination in Europe - everyone has hurried to look for culprits. It has not been very difficult to find some. The mismanagement of Josep Maria Bartomeu’s previous board of directors has been one of the main triggers for this crisis. But we would be wrong if we think that the main cause is to be found in the people who run the club. If so, a new president or a new coach might be enough to reverse the situation. Nor it seems that the situation can be addressed through relying on a certain style of play and certain values, a factor that has been considered key to explaining the club’s recent successes. The current problem is much deeper and goes beyond managers and philosophies. There are structural factors, eradicated in the recent political economy of Europe, which can explain more accurately Barça’s rise in the early 2000s and its decline in recent years.

The rise and fall of FC Barcelona in the last two decades is largely due to the adaptations of national and European leagues to the globalization of football. These adaptations, carried out in the form of various laws between the late 1990s and early 2000s, would decisively change the design of domestic and continental competitions, creating winners and losers across Europe. Barça was one of the main winners of the new competition structure. And the losers were many European clubs that, for reasons far away from their sporting management or the values they preached, would be relegated to continental anonymity.

Winners and losers of globalization

In the mid-1980s, the most powerful football teams were territorially distributed across the European continent. Teams such as Ajax, Benfica, Steaua Bucharest, Anderlecht, Gothenburg and Celtic Glasgow could compete against any team in the Spanish, English or Italian leagues. Football’s adaptations to globalization in the early 90s produced the first losers in Eastern European clubs. Eastern economies were at their weakest during the entry into force of the Bosman Act, which allowed the free movement of footballers between clubs in countries belonging to the European Union (EU). Clubs in Eastern Europe, not yet part of the EU, would not benefit from free movement until 10 years later. In the West, many vacancies for extracommunitarian players were released after the Bosman’s ruling. The greater economic potential of the Western European clubs and attractiveness of their leagues would drain players from Eastern competitions. Clubs like Red Star or Sparta Prague, to name a few, would lose competitiveness and disappear forever from the Champions League finals. As can be seen in the following Figure 1, the number of Eastern League clubs that have played in the quarter-finals (QF) of the UEFA Champions League (ECL) has dropped dramatically since early 90’s.

.](https://www.jordimas.cat/post/2021-12-12-fcb-rise-fall-eng/index_files/figure-html/ucl-east-1.png)

Figure 1: Teams from Eastern European clubs in UCL QF | Source: UCL dataset v1.

Adaptations to the globalization of football would also produce winners and losers within national leagues. In the 1990s, the globalization of telecommunications brought cable television and digital platforms to Spain. With these platforms came succulent benefits generated by selling the TV rights across the world. Each national European league decided the way the pieces of the cake were distributed among its clubs. In England, clubs would agree to negotiate rights collectively, making it possible for the highest paid club to earn less than twice as much as the lowest paid club. This made it possible to distribute the benefits of the globalization of football in a balanced way and to ensure that there were no big winners or big losers from these new revolution. In Spain, on the other hand, the negotiation of rights would be carried out individually. The approval of the individual negotiation of rights under the Professional Football League would in a few years produce great inequalities in the distribution of television rights revenue among La Liga clubs. If in the mid-1990s Real Madrid and FC Barcelona’s TV rights income was three times more than an average La Liga club, by 2005 their earnings were ten times superior.

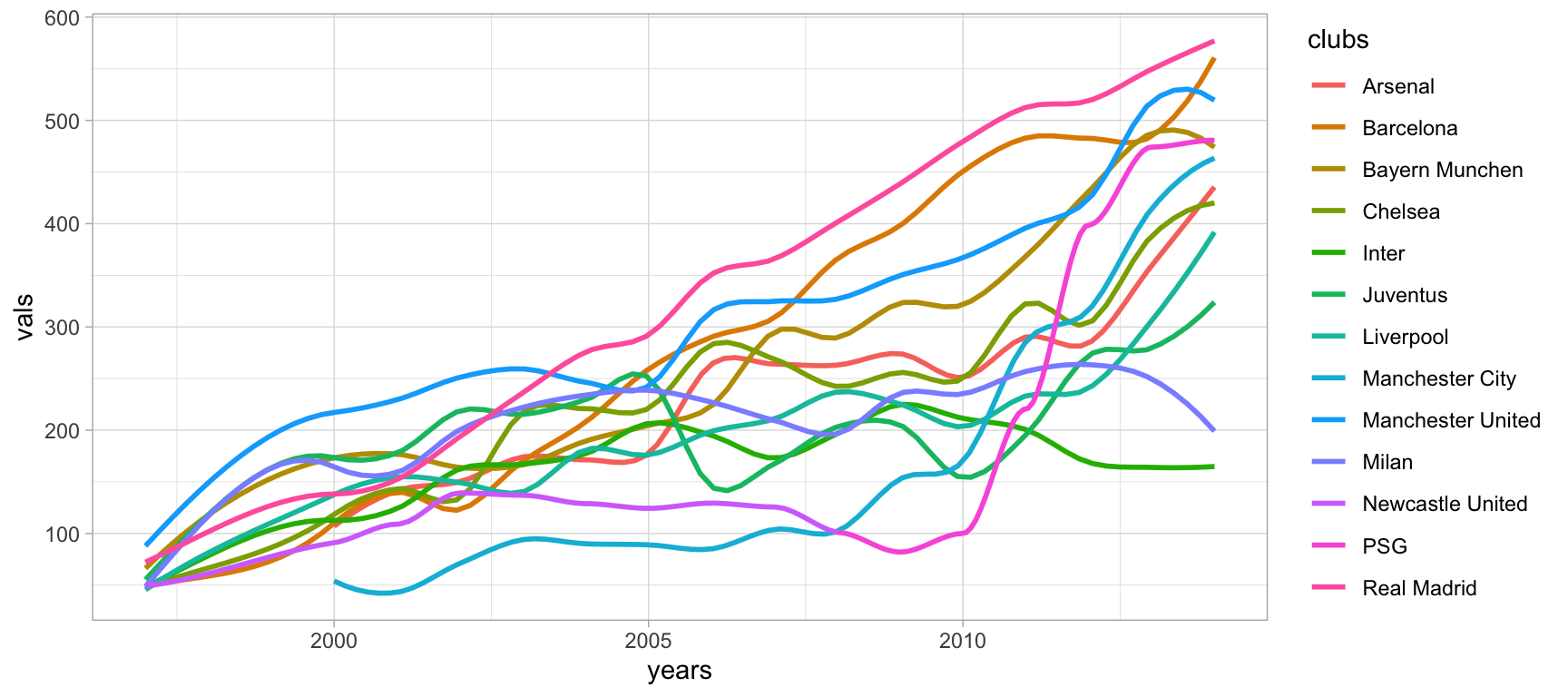

The hegemony of Barça and Madrid in the Spanish league for the last 15 years, with 100-point leagues and historic thrashings of all their rivals, is explained by the way in which the benefits of television rights were distributed in the 1990s. Unlike many other European leagues, the distribution in Spain ended up producing an unequal league. In the short term, it generated two of the clubs with the highest economic potential in Europe, but it would also undermine the competitiveness of the Spanish league, which in the long run has reduced its international appeal to the detriment of leagues such as England. Figure 2 shows that, even before winning the 2006 Champions League, FC Barcelona was the second club with the largest budget in Europe.

Figure 2: Evolution of largest European clubs’ budget 1997-2018 | Source: Deloitte

Big clubs from small leagues would also be part of the long list of losers in the globalization of football. The negotiation of television rights at the national level meant that small market leagues such as the Dutch, Danish and Belgian leagues had relatively much smaller cakes to distribute among their clubs compared to the major leagues in Europe. Thus, historic clubs such as PSV Eindhoven, Gothenburg and Glasgow Rangers would generate less revenues and ended up playing a smaller role on the European map. Since the middle of the 90s, only clubs from the six major leagues with the largest market -Spanish, English, German, French and Italian- will arrive to the final stages of the Champions League. As can be seen in Figure 3, only the clubs from one small league, the Portuguese - with a strong following in Brazil and other ex-colonies -, have reached the quarter-finals regularly.

.](https://www.jordimas.cat/post/2021-12-12-fcb-rise-fall-eng/index_files/figure-html/ucl-small-1.png)

Figure 3: Teams that do NOT come from the five major national leagues in the UCL QF | Source: UEFA Champions League (UCL) dataset v1.

Without any opposition in the domestic league, in the East, and in the minor leagues, the only European opponents of Real Madrid and FC Barcelona for almost 20 years were a few clubs in a few major leagues. The competition among them would also be uneven when, in the early 2000s, Spanish league clubs benefited from the so-called Beckham Act, which granted tax cuts to higher incomes and allowed Spanish clubs to offer salary conditions unattainable in other European leagues. Thus, the best players in the best leagues in Europe would play in Spain. Not only Beckham himself, but footballers like Ronaldinho, Henry and Cristiano Ronaldo would leave their clubs to join Barça and Madrid. Eight of the top 15 highest paid players in Europe played for both clubs in 2010.

The new globalization of football

FC Barcelona’s history over the last two decades has been strongly conditioned and benefited by the adaptations of the national and European leagues to the globalization of football. Without them, the club’s recent successes could not be understood, nor can its current crisis. The conditions that favored Barça’s rise have partially disappeared. The distribution of television rights in the Spanish league is still very uneven, but slightly lower than in previous years. The arrival of sheikhs and their petrodollars has allowed some European clubs to outperform Barça and Madrid in economic capacity. Spain no longer offers juicy tax incentives, which has made it difficult to retain players like Neymar or the signing of players like Verratti. And the interest in the Spanish league has relatively diminished, spurred on by the lack of competitiveness in recent years that have managed to maintain leagues like the English.

FC Barcelona’s current situation has not only been caused by mismanagement, but also by a changing context which, although it was clearly favorable for almost 20 years, now is more adverse. The club’s success was attributed to spurious factors such as the commitment to certain values and a style of play, completely ignoring the effects of a long-standing domestic and European competition system. Continuing to ignore the causes of such success can only lead to bad prescriptions when it comes to reversing the current situation.