The observation

Political conflicts with ethnic / national roots (may) cause ‘foot-voting’

Literature of foot voting (1)

In decentralized political systems

Tiebout (1956): Migration (foot-voting) as a mechanism to reveal voters’ preferences.

- Change of jurisdiction because other combinations of economic public goods (policies and taxes) are preferred.

- Due to inefficient governments (FF literature).

- Due to individual socioeconomic characteristics.

Literature of foot voting (2)

In decentralized political systems

Hirschman (1970): Trade-off between voice (ballot-voting) and exit (foot-voting).

- Vote and exit are not always negatively associated (Brubaker 1990; Hirschman 1993).

- Mediated by loyalty (barriers to exit): high factor mobility, attachment.

Literature of foot voting (2)

What do we know about non-economic factors?

- Loyalty: one size fits all? Attachment to country.

- Electoral system (Bolton and Roland 1997).

- Repressive systems (Hoffmann 2006, 2010; Burgess 2012).

Beyond economic public goods

Ethnicity shapes individual identity, which in turn affect voters’ preferences (Akerlof and Kranton 2000; Chandra 2005; Glaeser, Sacerdote, and Scheinkman 2003). Two mechanisms:

- Under/overprovided identity public goods diminish/increase individual’s utility (Akerlof and Kranton 2000; Pagano 1999).

- Polarization boosts preference revelation (McCarty 2019; Guntermann and Blais 2020).

Hypothesis

Four working hypothesis:

- H1: Existing trade-off between voice and exit. Within jurisdictions, discontents decide to vote with the feet instead of vote with the ballot.

- H2: Foot voting will be stronger in jurisdictions with high presence of independentism, since Spanish identity goods will be (socially / politically) under-provided.

- H3: Foot voting will be stronger in jurisdictions with higher polarization over the territorial question, since preferences are more likely to be revealed.

- H4: Ballot-voting and foot-voting are complementary in time, expecting thus that exit will increase in the long run in jurisdictions where voice increases in the short run.

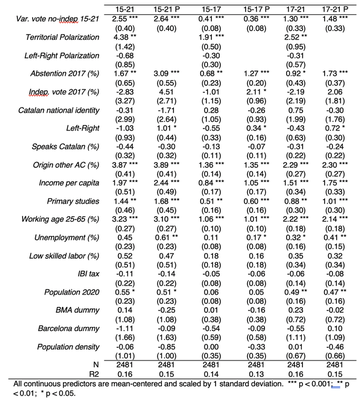

Methodology

- Data of migration from Catalonia to Spain at census section level (near 3.000 observations, 85% municipalities, 55% population).

- Since 2015, parties and voters are clearly defined in terms of national identity and their position towards the territorial question (periods 2015-17 and 2017-21).

- In each jurisdiction, polarization is calculated using the number of votes received by each party and their position in the territorial question.

- Presence of independentism as votes to independentist parties.

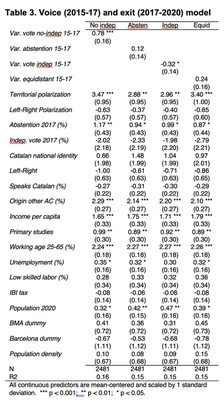

- For H4, we compare voting of 2015-17 with migration of 2017-21.

Results (1)

Results (2)

Conclusions

- We observe both voice and exit at the jurisdiction level, which might suggest that preferences are activated.

- Such activation may be explained primarly by the fact that high polarization exists in the jurisdiction over the territorial question and that citzens’ loyalty is low (have their origin in Spain).

- Exit has no association with abstention, independentist or equidistant voters (see Annexes in the document).

- Difficult to reach conclusions on H4.